Moral panic intensified after a paper published in Science in 2002 found that MDMA caused permanent brain damage in monkeys and baboons – two unlucky animals died from their doses – which did much to advance the stereotype of burned-out rave kids. (Most fatalities were caused by dehydration or combining MDMA with other substances.) It’s been a long journey for MDMA, once demonized by sensationalist media coverage that turned the rare ecstasy deaths into moral panics, often without mentioning the other factors that made the drug more dangerous. Photograph: Fairfax Media Archives/Getty Images FDA approval for therapeutic use could come as early as next year.ĭifferent forms of MDMA available on the market. That cycle may have already started: three clinical trials have found that MDMA, which is also called ecstasy, can speed the recovery of PTSD. Nuwer believes that MDMA will “follow the path of cannabis”, becoming legal medicinally first, then decriminalized, and perhaps fully legalized for all types of use. This book is for anyone who’s interested in the drug, whether it’s someone who’s taken it 500 times on the dancefloor or who’s using it therapeutically for the first time.” “I wanted to bring together the history, culture, politics and science of the drug all in one place. “MDMA deserves its own story,” Nuwer said. While cannabis and psilocybin have undergone rebrands of late, going from countercultural tokens to the mainstream, she believes that the public is starting to open up to MDMA, too. Nuwer is a science journalist who covered clinical trials for MDMA use in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We propose that high neurogenesis levels negatively regulate the ability to form enduring memories, most likely by replacing synaptic connections in preexisting hippocampal memory circuits.According to Rachel Nuwer’s book I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World, Resnikoff and his girlfriend’s romp was the first-ever documented instance of people taking MDMA recreationally. Interestingly, the decline of postnatal neurogenesis levels corresponds to the emergence of the ability to form stable long-term memory. Infants (humans, nonhuman primates, and rodents) exhibit high levels of hippocampal neurogenesis and an inability to form lasting memories.

Here, we propose a hypothesis of infantile amnesia that focuses on one specific aspect of postnatal brain development-the continued addition of new neurons to the hippocampus. Biological explanations of infantile amnesia suggest that protracted postnatal development of key brain regions important for memory interferes with stable long-term memory storage, yet they do not clearly specify which particular aspects of brain maturation are causally related to infantile amnesia.

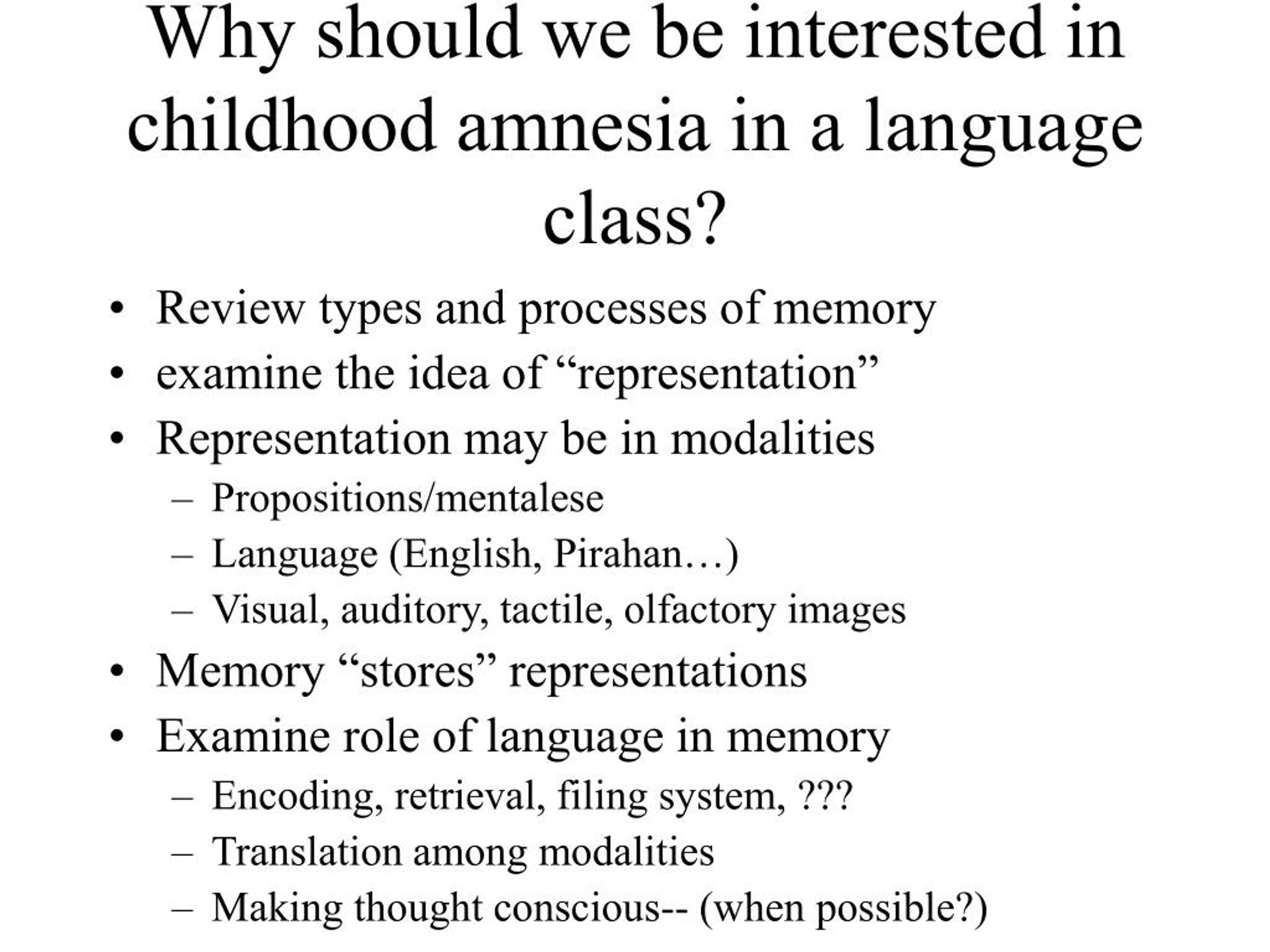

Psychological/cognitive theories assert that the ability to maintain detailed, declarative-like memories in the long term correlates with the development of language, theory of mind, and/or sense of "self." However, the finding that experimental animals also show infantile amnesia suggests that this phenomenon cannot be explained fully in purely human terms. How can these findings be reconciled? The mechanisms underlying this form of amnesia are the subject of much debate. Although universally observed, infantile amnesia is a paradox adults have surprisingly few memories of early childhood despite the seemingly exuberant learning capacity of young children. In the late 19th Century, Sigmund Freud described the phenomenon in which people are unable to recall events from early childhood as infantile amnesia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)